Why Development Institutions Should Recognize the Right to Know Day

A Case for the Inter-American Investment Corporation

by Alexandre Andrade Sampaio and Ishita Petkar

September 28th marks Right to Know Day — a day when the international community comes together to celebrate and emphasize the importance of access to information for all people.

Such celebration is even more important at a time when civil society organisations and communities face increased difficulties in accessing information and participating in development processes around the globe, with their fundamental rights being disregarded by governments and corporations.

In the context of development, the “right to know” is critical in ensuring that projects stay true to the promise of what development should be — to improve the lives of all people.

Truly sustainable development should be designed and lived by the same people, and exchanging comprehensive, accessible, and timely information among all actors is a necessary prerequisite. That is the reason why this right has been called “the oxygen of democracy”.

For real development to take place, there is a need to engage meaningfully with those involved in ongoing and iterative dialogue and exchange of information, starting with a community’s development priorities and throughout the investment cycle, in the spirit of partnership. Only then can projects and policies secure real benefits to local communities, in accordance with their own plans and priorities. When development finance institutions, governments and companies engage communities and civil society throughout the project cycle as partners, they encounter opportunities that can have positive development outcomes and avoid risky activities that can carry unduly adverse impacts. Conversely, designing and implementing projects without the meaningful involvement of communities and civil society can devalue and sideline local knowledge, priorities, and plans for development. Such a process could not be regarded as a pursuit for real development.

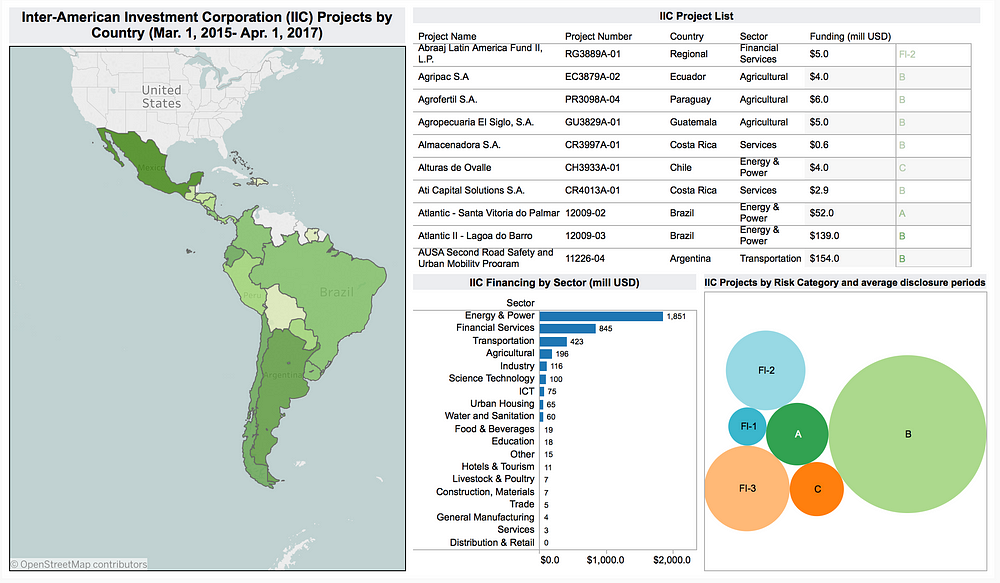

Despite this, the policies and practices of some of the most prominent development finance institutions do not reflect the importance of access to information rights. A recent analysis conducted by International Accountability Project (IAP) shows that the practice of the Inter-American Investment Corporation (IIC), the private sector lending arm of the Inter-American Development Bank Group (IDB Group), falls considerably short of best standards and practices.

For example, in the absence of access to information and proper participation, communities affected by the construction of the IIC-financed Hidroituango Dam in Colombia have faced drastic consequences for years, including being forcibly displaced and losing their livelihoods to a dam.

”In Colombia, the decision to build the biggest dam of the country in Ituango was imposed on local communities.”, says Isabel Zuleta of Ríos Vivos Antioquia — a movement working with those negatively affected by the Hidroituango Dam project.

As Isabel further explains: “The IIC is providing $450 million of financing for the dam and misled communities by not providing ways to fully participate in the decision-making process, and access information about adverse impacts. Also, the government has criminalised opposition to the dam.”

Unfortunately, such impacts on communities affected by so-called development projects are far from being an exception, and while virtually all projects are imposed by those with the power to make decisions on those communities, it can be difficult for some to see how this process can change in the near future.

Communities should be regarded and treated as partners, not subjects, in the development process — stakeholders who set the priorities of development in their regions, and who have a role in designing the projects that will ultimately affect their lives. To return development to its root purpose, respecting the right to access information is pivotal in ensuring meaningful and effective participation. These are universal rights emanating from the right to freedom of expression, secured by Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and replicated in international and regional treaties.

When analysing the current practice of the IIC at the time of disclosure, IAP noted that only 10% of Category B projects — those the development finance banks rate as the second highest degree of social and environmental impacts — had social and environmental studies available for impacted people to consult. Additionally, there was no information publicly available notifying communities about when and how they would be consulted, how they could lodge grievances at the local level, and that they have the opportunity to seek recourse for harms through the bank’s grievance mechanism. Even if the information was made publicly available on the bank’s webpage, there is no guarantee whether or not it would reach communities affected by the investments. For example, the Ríos Vivos Antioquia movement who monitors the Hidroituango Dam very closely, had never heard that the IIC was considering investing in this project. Development finance banks consider this dam a Category A project, which carries the highest potential for negative social and environmental impacts — as the ongoing consequences suffered by many confirm.

“The poor access to information practice of the IDB Group has made it difficult for us to inform communities in Argentina about potential impacts of projects coming their way” says Gonzalo Rosa from the national human rights organization, Fundación para el Desarrollo de Políticas Sustentables (FUNDEPS).

Partially to blame for the IIC access to information practice that falls short of international best standards is the current policy guiding the bank’s work. As recommendations supported by global civil society organisations worldwide demonstrate, the IIC’s current access to information policy contains problematic provisions and considerable gaps. These include contradicting well-established access to information principles, and prioritising clients’ interests over those of the public, restricting access to information with overly broad criteria, and allowing for information to be withheld when the reputation of clients and member countries are at risk.

“This means that information about human and environmental rights risks and violations could potentially be kept secret by the bank, in contravention of the very reason why the right to information should be complied with”, emphasises Gonzalo from FUNDEPS.

The IIC policy also fails to take into account the majority of access to information principles endorsed by expert individuals and organisations, which provide for, among other things, a limited scope of exceptions to access to information and for the protection of whistle-blowers.

Unfortunately, the IIC is not alone in cultivating poor access to information practices. Other development financiers such as the BRICS-founded New Development Bank (NDB), Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the Dutch National Development Bank (FMO) follow suit, with access to information policies that merit detailed analysis and criticism.

“The right to information remains to be an elusive objective in ADB’s proposed Access to Information Policy if it will retain its exhaustive list of exceptions to disclosure. These restrictions on financial information and internal audit reports remain inaccessible from public access and raise questions on ADB’s accountability,” according to Rayyan Hassan the Exective Director of NGO Forum on ADB, an Asian– led network of civil society organizations, who monitors the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

Later this year, the IIC is expected to commence its consultation period to revise its access to information policy. It is rumoured that this process will last for only 90 days, a short period for proper participation of the entire American continent affected by the operations of the bank.

This consultation process, which should be constructed in a participatory manner, should be long enough to provide stakeholders with sufficient time to properly participate in such an important and technical discussion. The establishment of a formal, inclusive, robust, and transparent consultation process throughout the region to harness the experiences and insights of civil society groups and communities would be much welcomed.

We invite communities and civil society organisations to join us in the IIC consultation process by telling your stories and making the case for better policy to guide the IIC in its work.

The adoption of improved standards and practices on access to information at the IIC would be reason to truly celebrate this Right to Know Day.

Alexandre Andrade Sampaio is the Policy and Programs Coordinator at International Accountability Project based in Brazil.

Ishita Petkar is the Community Engagement and Policy Coordinator at International Accountability Project based in Washington, DC.