Around the world, countries have geared up for an influx in investment and development as the global community reaches to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. It’s already been decided that investments in infrastructure, transport, and renewable energy are prerequisites for “development”. Yet, despite decades of mistakes to learn from, the methods employed to achieve this new agenda are old. Those who stand to benefit — and lose — the most from “development” continue to be excluded from its decision-making processes.

A pertinent example of this can be found in the significant number of regional “master” plans and projects being proposed and executed worldwide. One Belt One Road, South American Council for Infrastructure and Planning (COSIPLAN), Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA), China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) — the list goes on. Some are older, some are new. All share the same lack of transparency, access to information, and meaningful participation of those whose lives will be impacted.

For many of these massive plans and projects, it is difficult for civil society and communities to find information on the financiers and actors involved, or even the proposed locations for construction. Based on the information that is available, its inaccessibility makes piecing together a complete picture of an individual project’s role in a larger master plan unrealistic for communities that might be affected. Without access to information, it is impossible for communities to meaningfully participate in consultations, seek remedy, or contribute to project designs that further their development priorities. The SDGs are “for people, planet, and prosperity” — in that order. Placing the welfare of people at the beginning, heart, and end of all development projects is necessary if the global community is to achieve this ambitious agenda.

The Early Warning System (EWS) can play an important role in helping ensure communities have the information they require to assemble a coherent picture of proposed development projects, and have the opportunity to influence their design. The EWS uses projects proposed by international finance institutions (IFIs) as an entry point. Operating on public money, IFIs are beholden to constituents to ensure they disclose adequate information about their projects. In practice, the availability of complete and accessible information varies among IFIs, with significant improvements needed by all. Despite these limitations, by tracking all projects proposed by 13 different IFIs, the EWS is able to connect projects that are related, capturing a partial image of complete regional plans or projects.

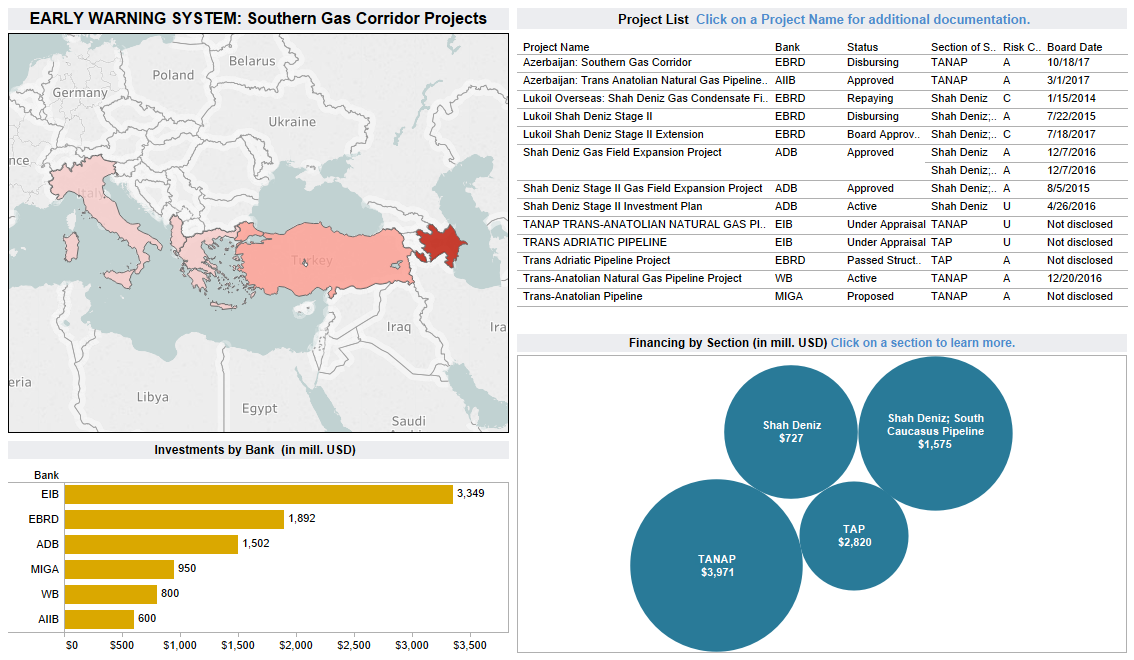

For example, for an event held during the World Bank’s 2017 Annual Meetings, IAP analyzed the Southern Gas Corridor to support partner Crude Accountability’s efforts in bringing justice to communities affected by the development of the Shah Deniz gas fields in Azerbaijan — the source for the Corridor. In addition to Shah Deniz, the Corridor itself is made up of three separate pipelines: the South Caucasus Pipeline (SCX) crossing Azerbaijan and Georgia; the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) crossing Turkey; and the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) crossing Greece, Albania, and Italy.

“They informed us that they are going to build a school for us, that they will pave a road, and will provide us with jobs, prior to launching the terminal. But it was just a promise, nothing happened.” — Ezimkend community member affected by the Shah Deniz project

According to the official TAP website, the Corridor is “planned infrastructure projects aimed at improving the security and diversity of the EU’s energy supply by bringing natural gas from the Caspian region to Europe.“ While the EU is advertised as reaping the benefits of a stable natural gas supply, communities in the Corridor’s path are left not only without the fulfillment of their development priorities, but further impoverishment.

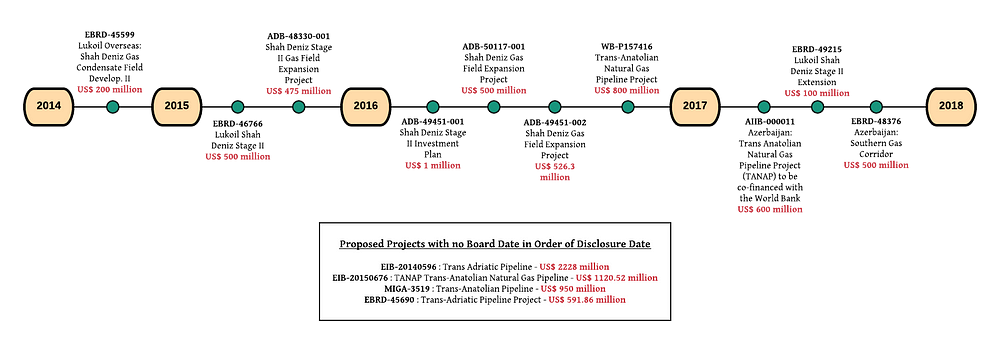

Using data collected by the EWS, we tracked the investments made and proposed by IFIs in the Corridor since 2014:

Laying out the projects in this timeline organized by Board date, it quickly becomes apparent that investments in the Corridor have increased since the beginning of 2016, and that there is an enormous amount of money flowing out of institutions aimed at “development”, for the construction of a Corridor that is impoverishing the lives of the very people IFIs are mandated to benefit.

The data from the EWS also revealed the amount of financing coming from each bank, for each section of the Corridor: http://bit.ly/SGCorridor

Albeit presenting a partial picture, the EWS is able to pierce the opacity of these large regional projects and share a wider and more accessible view of projects with communities that might be affected. The Southern Gas Corridor is an example of a more compact regional infrastructure plan, but using the architecture of the EWS, we can better track and share the individual pieces of more sprawling master plans to help equip communities to connect with each other, respond to unfavorable projects, and influence their designs according to their priorities.