Fisherfolk Communities in Northern Sri Lanka Organize to Protect Livelihoods

Fisherfolk Communities in Northern Sri Lanka Organize to Protect Livelihoods From Proposed Asian Development Bank Project

By Tom Weerachat

Earlier this year, I found myself in the quiet town of Jaffna, in Northern Sri Lanka, sharing a meal with fisherfolk from different parts of the northern province. We were seated in a newly built hotel in the middle of town, surrounded by war-torn buildings and ruined historic palaces. Our meal consisted of a simple yet delicious fish curry, served with rice and topped with spiced coconut meat. The food was unlike anything I had tasted before, unique to the region and distinctive in flavor. My companions explained that while they currently had access to abundant fish from the sea, they worried they would lose their traditional foods and livelihoods as a result of a new development project that was being proposed by the government.

This development project was the reason why I was in Jaffna in the first place. A few months ago, through the Early Warning System, I learned about a new proposal for a project, the Northern Province Sustainable Fisheries Development Project, that would be funded by the Asian Development Bank. The project included plans to build harbors, anchorages, and associated facilities with the objective of introducing new fishery technologies and expanding aquaculture in Jaffna and other nearby districts. These plans, however, pose significant risks to local communities, a majority of whom rely on fishing or fishing-adjacent activities for their livelihoods. If the project is implemented as it is currently designed, local fisherfolk communities would lose control over their fishing ground, women would lose their jobs and 350 or more single-day boats would be displaced.

As I read more about the project, I was shocked to see that documents weren’t available in Tamil, the language that is spoken by a majority of residents in the Northern Province. This was especially a cause for concern, given the recent history of this region. This part of Sri Lanka had sustained severe damages from the 26-year civil war between the government and the separatist group, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). After the end of the conflict in 2009, these areas that had previously been inaccessible as a result of the war started seeing an influx of investments and development projects. This project, proposed by the government of Sri Lanka and funded by the Asian Development Bank, would be one of the first major developments in an area where people have little experience with large-scale development.

To share information about this project, I reached out to the Sri Lanka Nature Group (SLNG), a member of the civil society network, NGO Forum on the Asian Development Bank, that was based in Colombo. SLNG had worked in the Northern Province previously, to support communities in the aftermath of the catastrophic tsunami in 2004 and continues to work with communities in the region.

“We heard from the government that there will be development on fisheries and harbors in the area but they said the details will come later. After we learned from the Early Warning System that the Asian Development Bank would be involved in this project, we contacted communities and informed them about the plans.” explained Thilak Kariyawasam, the director of SLNG.

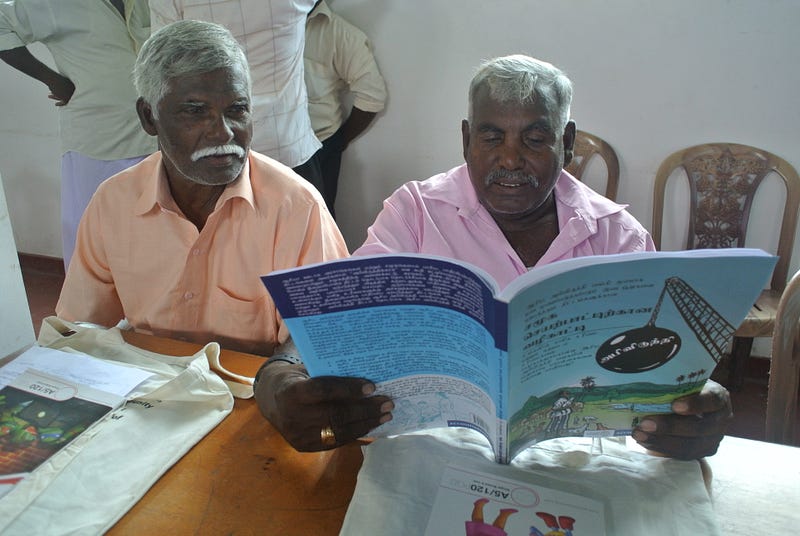

Community members expressed serious concerns about the project and requested more information about the project and its financiers, including advice on how to organize to protect livelihoods and human rights. To respond to these concerns, SLNG, Accountability Counsel — a U.S. based legal organization — and the International Accountability Project traveled to Jaffna to facilitate a workshop with affected communities. The workshop was attended by a diverse group of community representatives, including women, youth, community elders i.e. the groups who would be disproportionately impacted. We provided project information in Tamil and discussed the proposal and its potentials impacts. IAP’s Community Action Guide to the Asian Development Bank was translated into Sinhaleseand Tamil and shared with participants to shed light on the bank’s safeguards and to share the experience of other communities who faced similar struggles.

We were surprised to learn that most community members had only heard about the project through SLNG and that no one from the government or Asian Development Bank had reached out to inform them about the plans. We also learned about community members’ lives and livelihoods, living so close to the sea. Participants mapped out their communities, explained where they lived, where they found abundant fishing grounds and how they organized themselves as a fishing society. One young fisherman, now 19 years old, spoke of how he had started fishing at the age of 4. He worried that with this new project, he would lose the ability to fish and provide for his family. Another woman, a leader in her community, shared that for many widows who had lost their husbands to the war, fish processing activities were a major source of employment. A third participant proposed that the community also needed a warning system for tsunamis, something that is absent in their region.

As I listened to each participant’s stories, I was struck by how these suggestions would align with the objectives of the project proposed by Asian Development Bank. Yet, the project lacked any community-centered proposal. This wasn’t a simple oversight. In fact, nobody from the project team ever invited community members to share their ideas. One meeting had been organized by a project consultant but it was limited to only a few leaders from the local fisheries federation who were invited but not given the opportunity to offer any suggestions. Meanwhile, community members were not even aware that such a meeting had taken place and were unaware about project plans.

“You have an important opportunity to influence and suggest changes to the project and its design now; this is more likely to be successful at an early stage than after the project gets approved” explained Anirudha Nagar, South Asia Director for Accountability Counsel. He also shared examples of how other communities in South Asia have organized to respond to projects and in particular, used the ADB’s accountability mechanism to influence project implementation. I also shared an example of a successful intervention in the early stages when a community-led effort in Malawi helped avert the implementation of a harmful project. We discussed how project developers frequently claim that consultations have been organized with communities, without commenting on the nature of those consultations and if there good faith efforts to learn from communities and incorporate their priorities.

At the end of the workshop, we were able to collectively increase our understanding about each phase of the project and share information about how communities may be safeguarded by national laws and bank policies. I also witnessed a strong solidarity and commitment from each of participants not only to protect their home and their ocean but also willingness to take control of this development process.

Since the workshop, communities have carried out a number of activities to actively engage with decision makers. In April 2018, communities submitted a letter, with support of SLNG, to the Sri Lankan government and the Asian Development Bank expressing their concerns about the negative impacts of the project. In the letter, they demand that community members and fishermen cooperative representatives be included throughout each stage of the project and have ownership and management of project activities. Communities also request that the project support community participation, diversify fisheries activities and build the knowledge and skills required by local community for sustainable fisheries. Starting in June, communities with support from IAP and SLNG, have started their own community-led research process to better understand impacts and priorities. The research project will aim to identify community-led development proposals that can influence changes before the project is approved in the next few months.

Reflecting on my visit to Jaffna, I am struck at the remarkable resilience of local communities who have had to cope with so much over the past three decades. I recognize that the problems they face are not unique within Sri Lanka or even beyond it, but I remain inspired by the commitment of the women, men, youth, and seniors I met as well as the SLNG who continuously challenge unequal power relations within the current development model and work to take back control and shape the development they desire.